ABOUT THE C.G. JUNG FOUNDATION

Newsletter of the C.G. Jung Foundation of Ontario

ISSN 1918-6142

Chiron is a newsletter that exists to support the work of the C.G. Jung Foundation of Ontario. It was established in 1980, and has existed in electronic form since 2006. Its name and masthead image, adopted at that time, are drawn from ancient Greek culture. In Greek mythology, Chiron was the last centaur, a son of the titan Cronus. He was famed for his wisdom, knowledge and skill at deciphering the will of the gods, to healing effect.

Volume 34, No. 1 Summer 2014

Editor: Robert Black

| PDF version of this issue for easier printing |

Contents

- The 2014-15 public education programme

- News from the Analyst Training Programme

- Life after Suicide, by Robert Black

- OAJA member publishes new book

- Jungian Night at the Theatre: Burying Toni by Catherine Frid

- Book review: Helen Brammer Savlov, on Wearing my Feathered Hat, by Johanna Breyers

- Submissions to Chiron

The 2014-15 public education programme

From this year, the C.G. Jung Foundation of Ontario offers its annual course brochure in electronic formats only. Besides listing on the website, the brochure will be available in a .pdf for those who wish to print a “hard” copy for themselves.

Production of the 2014-2015 programme listings is well advanced, and should be on line shortly. Among several exciting new offerings is Jungian analyst Elisabeth Pomès both lecturing on the psychology of performance, and offering a seminar on performing without fear. As many readers will know, she is also a professional voice musician and judge. Beverly and Austin Clarkson put forward a workshop on giving and receiving, based on aboriginal models. Caroline Duetz offers a seminar on sugar, symbolic and physical. Other senior analysts offer the fruit of their years of working with Unconscious themes, such as Graham Jackson on the “War on Eros.”

As usual the programme is centred on the solid “meat” of Unconscious material, helping us to deepen our appreciation and knowledge of symbolic language. There are ample offerings on fairy tales, on poetry, on spirituality, on opera, on specific symbols as well as on the nature of the symbol, and the popular four-part “Jungian Fundamentals” series.

When the brochure is on line, we hope you will be pleased, and look forward to seeing you!

News from the Analyst Training Programme

Since the ATP began in 2000, much hard work on both sides has resulted in, to date, twenty-three graduates. Some of these have, since graduation, transferred from OAJA to other IAAP voting societies; but even so, with this graduation a clear majority of the members of OAJA are now locally trained.

The most recent graduation ceremony of the OAJA Analyst Training Programme brought two new analysts into the Jungian world. Here they introduce themselves in their own words:

22. Angela Pessinis

22. Angela Pessinis

Angela was born in Sparta, Greece, and after completing high school in Athens she immigrated to Canada. She has never ceased to be deeply connected to her homeland and its overwhelmingly rich cultural heritage. Canada, with its unique multiculturalism and immense land, has become her second home and permanent place of residence.

Angela studied English literature and humanities, comparative literature, at York university, which provided an excellent exposure to the depths and richness of the human psyche and its creative expression. It was in a literature course that she first came across Jung's Man and His Symbols and she was deeply impressed by its depth and Jung’s spherical approach to the human psyche. It was apparent then that she would have to return to Jung and explore more of his work. One of Linda Leonard's books brought her back to Jung's work a few years later. The book renewed her fascination with Jung's psychology and stirred up her interest in undertaking studies in the field.

Subsequently Angela managed to arrive at the Jung institute in Zurich and – immersing herself exclusively in lectures and seminars – felt like being at home and living a dream. After two semesters in Zurich, OAJA initiated the training program in Toronto which made studying easier as it became part of her daily life. The journey towards completing the studies has been rich and enriching. She had the privilege to work with wonderful people deeply committed and respectful to the psyche and to connect with colleagues.

The title of her thesis is "Olive Tree and Olive Oil: Agents of Change and Transformation".

Her interests include healing and transformation, creative energy, the manifestation of the psyche in all its expressions, interpretation of dreams, myths, fairy tales, film, literature and art in general. She presently lives in Montreal with her husband, where she has her practice which she finds deeply meaningful and fulfilling.

23. Andrew Sherwood

I knew that to be a Jungian analyst was my calling as I watched Fraser Boa’s film series The Way of the Dream for the first time, back in 1987.

Eros, relatedness, the delightful discovery of The Other is key to my navigation of inner and outer worlds.

I can not present myself in a meaningful way within the space provided here, thus I offer three of my favorite film quotes for you pleasure and interest. They may better position me than my own few words.

My words here are in invitation for those moved to do so, to contact me. If so inclined, please send an email and say hello. My contact information is available on the OAJA website Analysts listing page.

From David Lynch’s Blue Velvet:

Dorothy Vallens: I looked for you in closet tonight. It’s crazy, I know. I don’t

know where you come from… but I like you.

From Miranda July’s Me & You & Everyone We Know:

Michael: The best thing for that fish would be... if he could just drive

steadily... forever.

Christine: I guess these are his last moments of life. Shall we say

some words? I didn't know you... but I want you to die knowing that you were loved. I love you.

From Hal Ashby’s Harold & Maude:

Dame Marjorie Chardin: Aim above morality, otherwise you cheat yourself out of too much life.

Life after suicide

by Robert Black

Some weeks ago, I heard with a heavy heart that a student from twenty years ago had ended his life. He was in his early 40s. Anyone I knew who also knew him was not completely astonished, but we were taken aback. His crowded but conventional funeral service struck many of us as recalling a person – a persona, perhaps – that we from so long ago had not known.

What was most powerful for me was the heartbreak and the injured souls of that circle of which I was a part. Since then, I have reflected on some of what C.G. Jung and his community offer on suicide, but most particularly on life after suicide – comfort to us who are left behind.

Jung’s two volumes of published Letters are scattered with accessible reflections on this heavy topic. In many ways, Jung the lover of souls is closest to the surface in his letters. He never underestimated the ordeal that life presented for some, and the sheer tsunami of despair that at times seemed to force their hand. But even while apologizing for his “incompetent reflections,” he made much of the indications he found throughout his work with the unconscious that our life is an interlude in a long story, “an experiment which we have not set up” (10 July 1946).

The vital work indicated by suicidal ideation, for Jung, was to see and to understand the shadowy – the murderous and criminal – tendencies that are very frequently encountered both in ordinary life and in the attempt to do serious psychological work. (Vol. 2, 25f., 13 October 1951) Part of what we do, in encountering the unconscious with a guide, is to drag “a tremendous unconscious fantasy system” – part of what Jung called Shadow – “into the light of day with unspeakable effort and patience.” (Cf. to Freud, 12 June 1911, Vol. 1, 23)

Every day – every hour of every day – even more frequently – it is the lot of some souls to experience dark and self-destructive urges. To use an explicit image Jung shared in his autobiographical reflections, keeping one’s tiny candle lit and protected on one’s journey, despite the dark winds of difficulty and demand, can seem impossible. The pull towards an early death – “letting oneself off the hook” – can seem irresistible. Jung did sympathize with thoughts of suicide as natural death approached, and sometimes marvelled “that I could fight my way through the inimical jungle.” (Vol. 2, 489, 5 March 1959) But in the end he pushed such thoughts away. Suicide “is murder and a corpse is left behind, no matter who has killed whom.” (Vol. 2, 279, 19 November 1955; cf. 13 October 1951).

But as we see every day in dreams and elsewhere, life can “turn on a dime.” The marvels that one encounters in the unconscious show, again and again, that life is very precious, therefore as he says to be “scooped up” so long as possible.

Anything that gives us joy and satisfaction in being alive is something to be cultivated. Especially with the insights that come from analysis, we can slip past the dragon, escape from the ogre, and evade the net or the trap. Cobwebs may cling, but not forever.

Even as life’s challenges increase and our bodies fail us, there is hope. Jung was once asked on camera about aiding the end of life. His reply is full of the wisdom and hopefulness that can still reach us, almost sixty years after he uttered the words:

Life behaves as if it were going on and so I think it is better for old people to live on. To look forward to the next day – as if he had to spend centuries. And then he lives properly. But when he is afraid and he doesn't looks forward, he looks back, he petrifies. He gets stiff and he dies before his time. But when he’s living on, looking forward to the great adventure that is ahead, then he lives.

This optimistic and encouraging view comes in some measure from the encounter, alluded to earlier, with those tendencies that thwart the realization of the Self. That encounter is safest done, it seems to me, in the company of an analyst. For it is hard, tricky, slippery psychological work, of necessity requiring clear-headedness or at least the company of other like-minded people. But through it, we learn that prisons can be breached, and dragons slain. Jung’s view also grows out of the encounter with the sheer power of the life urge. There is life? Then there is hope. We can trust that, at its core, Life is “the great adventure.”

There is a very concrete image, a gift of the unconscious, which can help us reconnect with life after a suicide. Marie-Louise Von Franz offers us the student memory of her rooming house, where a sixteen-year-old with her nurse also resided. One night, she dreamed of a terrible explosion and of crouching behind a wall with that nurse, “in order not to be hit by stones and lumps of earth flying about.” She awoke in the morning to discover that the sixteen-year-old had taken her own life.

In another remembrance of the same or perhaps a similar event, she referred to the image of a tree exploding in the forest, taking with it some of the roots and canopy of the trees around. This is a vivid way of seeing that we who are left really have been injured, too.

As Von Franz put it, the girl’s life energy was not “used up naturally” but rather had been “released suddenly.” Thus her environment was dangerously disturbed – and if you found yourself in that environment, the only sensible thing to do at first was take shelter – to hide – until everything had settled back down. (On Dreams & Death, page 84.) To amplify from the second image (whose source I have not relocated), the next matter was healing from the injury thus caused. Some part of us is gone, and that is a fact with which we have to come to terms.

No one in this life is competent to judge those who have taken their lives. But we can, and should, consider the damage they have done to us. If for us there is to be life after suicide, first hiding, then healing and eventually habituating ourselves (and who knows, forgiving them?) all seem called for. Only following that comes a return to our own existence – vividly aware, perhaps, how precious it is – and to our own sustained encounter with the forces of darkness, and with the call to “the great adventure.”

OAJA member publishes new book

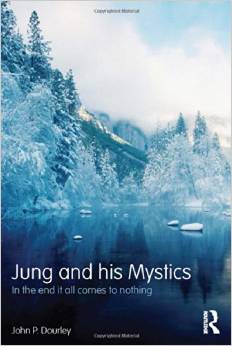

John Dourley, Jung and his Mystics: In the End It All Comes to Nothing. Hove, UK: Routledge, April 2014, ISBN 0415703891.

John Dourley, Jung and his Mystics: In the End It All Comes to Nothing. Hove, UK: Routledge, April 2014, ISBN 0415703891.

John Dourley is a senior Jungian analyst and professor emeritus of Carleton University in Ottawa. He has recently published a book in the UK aimed at scholars and senior research students in Jungian Studies. It will be necessary reading for those interested in the connection between religious and psychological experience.

Dourley examines the influence of mysticism on Jung’s psychology and thought, in particular the apophatic stream from the 13th century Mechthild of Magdeburg and her fellow mystics the Béguines, through Meister Eckhart to Jacob Boehme, finally to Hegel in the 19th century and Jung’s Answer to Job in the 20th.

This adjective, “apophatic,” will probably be as unfamiliar as its opposite, “cataphatic.” In theology, these terms were (by way of shorthand) applied to our understanding of God as “negative” or as “positive.” Cataphatic theologians would talk of what God is, such as love, mercy, etc. They and their approach are behind a great deal of what passes as knowledge in our civilization. Apophatic mystics, on the other hand, say that human language is too limited – to finite – to describe Something that is totally Other. They experience the divine by regression beyond all form, formal expression or immediate activity.

Dourley makes this relevant by concluding that Jung's understandings of the psyche, informed by apophatic mysticism, could greatly alleviate the conflict between faiths, religious or political, by drawing attention to their common origin in human depth. Whatever it is we perceive – God? God image? Self? – may well be beyond cataphatic expression. Only when we stand in the ruin of our words, when language fails, do we encounter God. It rather reminds one of Thomas Aquinas with his millions of words suddenly stopping and refusing to write any more. When asked why, he said, ‘It is all straw.’ And then he died.

As Prof. Dourley wryly says, “Not recommended for light reading, but the paperback has a nice cover.”

Jungian Night at the Theatre: Burying Toni by Catherine Frid

The Alumnae Theatre Company, at 70 Berkeley and Adelaide in downtown Toronto, presents Burying Toni, a new play by Toronto playwright, Catherine Frid. In this exploration of the inner world of Emma Jung, we discover how she grapples with her imagos following the funeral of her husband’s long-time mistress, Toni Wolff.

The “Fireworks Festival” is an offering of new plays developed at Alumnae. Frid’s play is part of this, and will be enacted eight times between November 13 and 29. The playwright will be giving a special presentation on Saturday, November 22. Tickets are $15, and on Saturdays “pay what you can.”

Book review: Helen Brammer Savlov (Jungian analyst, Toronto & Durham region)

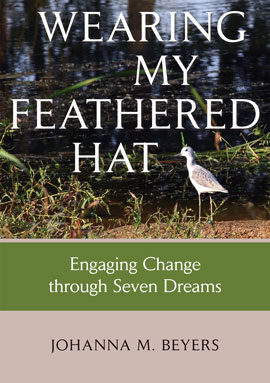

Wearing my Feathered Hat: Engaging Change through Seven Dreams, by Johanna M. Beyers. Wind Oak & Dove Press (2013).

This is a book written by Jung Foundation member Johanna Beyers that has taken some twenty years to come to fruition. In the acknowledgements we can find familiar names of analysts and scholars from the Toronto Jungian community amongst the therapists and teachers who have encouraged and challenged the writer to clarify her perspective. The result is a text that is both personal and also of universal interest because it draws on the experience of seven archetypal, “big” dreams that the writer received at key turning points during her life.

This is a book written by Jung Foundation member Johanna Beyers that has taken some twenty years to come to fruition. In the acknowledgements we can find familiar names of analysts and scholars from the Toronto Jungian community amongst the therapists and teachers who have encouraged and challenged the writer to clarify her perspective. The result is a text that is both personal and also of universal interest because it draws on the experience of seven archetypal, “big” dreams that the writer received at key turning points during her life.

In terms of its genre, this book is partly a memoire and partly the narrative of an individual woman’s quest to find meaning in her life journey as she struggles with the discourses of today’s church and science. It is also akin to an extended dream journal that many keep, alert to the personal associations. But this book becomes relevant to all of us as the writer explores the archetypal amplifications of her dreams that take the reader into the heart of the mystery of the living symbol. Moreover, with continual self-scrutiny, the writer searches to answer the questions of how to honour and respond to numinous dreams that stagger us with their power and awesome beauty. In so doing, this book becomes a work of religion in the sense that Jung uses this term:

“We might say, then, that the term “religion” designates the attitude peculiar to a consciousness which has been changed by experience of the numinosum” (CW11 para 9).

The book starts with an introduction entitled “Driftwood” that expresses the writer’s early approach to her life in which she was committed to the interior world of images and with the desire to “feel intellectually, emotionally and spiritually at home in everything I did” (p.4) but with no coherent idea of how to do this. Her outer world journey is briefly sketched from being an earth scientist with a doctorate in Environmental Policy to recent certification as a Sandplay Therapist but the enlivening core of her inner life and of the book is expressed in the following words, “Slowly I came to accept that my story does not exist apart from the dreams that fed it” (p.8).

The chapters that follow interweave their themes of initiation, healing and transformation while circumambulating around encounters with the Self through the extraordinary figures of the writer’s visions and dreams. The appearance of the first of the seven figures was at dawn on a geological field trip. Woken from sleep by a troop of wild coyotes, a vision unfolded of a majestic “luminously golden” grizzly bear who spoke directly to the writer. Reflections on the presence of ‘Grandmother Bear’ take the writer to the realizations of how “the holy is as inseparable from nature as pigments in a leaf or silica in crustal rocks” (p.63). After Bear, other figures followed, before a final dream encounter with a great Snake that was the last of the “big” dreams. The details of the intervening images I will leave for other readers to enjoy and wonder at.

The book is partly chronological but I found that each chapter can stand alone as a reflective essay separate from its fellows and be returned to, and read again in order to savour the many layers of meanings. Johanna Beyers is a poet and writes meditative prose that is best read slowly to allow time for her images to be taken in and for the reciprocating images that may arise in the reader’s psyche to take form and dreams to be recalled. There is an individual chapter devoted to a guided active imagination exercise entitled “Deep Time Fantasy” also to be explored.

I particularly liked the subtlety in the writer’s far-reaching amplifications of the dream symbols that come from a reverence to let the voice of the soul resound more loudly. Completely new for me – and I imagine for many Foundation readers – are the geological amplifications. Here Beyers shows herself to be a gifted teacher and I found myself carried along with her into new territory as she writes, “Geology entered my life as a revelation; I climbed through it as through a hole in order to find, like the ancients, the seed of my becoming” (p.59).

Chapter 8 “Snake’s Field” is the penultimate chapter, but for me, it is the culmination of the work. It includes a penetrating and moving meditation in which Beyers is at her best as she reflects on the inexhaustible mystery of the image of the Christ and the Virgin of her later dreams. The final chapter “A Sustaining Vision” completes her reflections on her personal journey to date and provides a thought provoking commentary on the quest for sustainability in the natural world seeing it as a “nascent collective image awaiting conscious realization” (p.231). I sense there could be another book in the making here.

For Toronto readers, the book is available at Caversham Books and Ben McNally's. Copies may also be ordered online at wearingmyfeatheredhat.ca.

SUBMISSIONS TO CHIRON

The C.G. Jung Foundation’s members and friends are very welcome to submit pieces for publication in Chiron. We would particularly welcome short articles (under 1000 words) on archetypal material, and very short (under 500 words) “book notes” and film reviews. Longer pieces can be negotiated, especially if serialization is possible.

We very sincerely promise that our responsibility to cast an eagle editorial eye over these submissions will be lightly and not impertinently applied, and that you will see beforehand any results of our meddling; so that the full essence of your insights and the character of your “voice” is kept safe and sound in the published version.

Hyperlinks in the electronic version of Chiron

Hyperlinks in the electronic version of Chiron do not imply or constitute endorsement of the organization or individual concerned, and are provided as a courtesy in current issues only. The C.G. Jung Foundation of Ontario is not responsible for the content of such sites.

Past issues available online

- Autumn 2013

- Spring 2013

- Autumn 2012

- Spring 2012

- Winter 2012

- Autumn 2011

- Summer 2011

- Spring 2011

- Winter 2011

- Autumn 2010

- Summer 2010

- April 2010

- January 2010

- October 2009

- Summer 2009

- April 2009

- December 2008

- January 2007

- September 2006